Samuel Insull: Father of Light Pt. IV

Downfall

Before you read this one, check out Part I, Part II, and Part III!

In 1926, Insull gave $160,000 to Illinois Republican Senate Candidate Frank Smith, who went on to win the party nomination in a hard-fought primary against Senator William McKinley. Before becoming a senator, Smith had served as the chairman of the Illinois Commerce Commission, which regulated Insull’s utilities. Perhaps Insull justified the obvious conflict of interest by telling himself that buying a senator was a calculated risk—one that would exact revenge against a long-resented political opponent and business competitor. To the public, however, Insull simply denied the obvious, stating that the Illinois Commerce Commission had “never granted any of my companies anything they were not strictly entitled to.” While Smith had never been “Insull’s boy”—he had blocked all of Insull’s rate hikes during his tenure as chairman, in addition to approving rate cuts totaling $42 million—the picture looked ugly.

The Senate protected its reputation against corruption allegations by refusing to seat Smith, nullifying his election, and launching an investigation into campaign corruption. The investigation spanned two years, during which newspapers dragged Insull’s name through the dirt from coast to coast. (News magnate William Randolph Hearst was a friend of Insull’s who assured him it wasn’t personal; but Hearst, the leading purveyor of “yellow journalism,” was never one to let mere friendship get in the way of sales). When the Senate committee brought Insull in for questioning, he initially refused to divulge his campaign contributions for fear that the evidence would damage the other campaigns he was bankrolling in upcoming municipal elections. The Senate held him in contempt of Congress, the consequences of which Insull dodged by releasing the details of his contributions himself—after the municipal elections, when the evidence could no longer hurt him or his politicians. He displayed no remorse and repented not at all.

Insull got off, but his growing success, combined with the visibility of his hand in political affairs, began to draw the ire of Progressive holdovers, including Senator George Norris of Nebraska. Norris was a die hard public power activist who despised the utility industry’s baronial influence on American life, calling the entire industry a “gigantic trust that has fastened its fangs upon the people of the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from the Great Lakes to the Gulf.” He spent the better part of the 1920s fending off private acquisitions of Muscle Shoals, a public hydropower dam in the Tennessee Valley, which had been built to power fertilizer production during WWI. The dam was finished after armistice, which left it mothballed. It was Norris who militated the Senate against seating Frank Smith. “God only knows how many Senatorial campaigns Mr. Insull has financed,” he said. When the investigation into Insull’s political influence in senatorial campaigns went belly-up, Norris turned his attention toward Insull’s other affairs. The Senate would authorize the Federal Trade Commission to begin what became a seven-year probe into the inner workings of the utility industry. Its results wouldn’t see the light of day until Insull was already on the brink of destruction.

But Insull simply couldn’t hear his political opponents gaining ground on him over the thunderous sound of his own success. He did, however, hear disturbing news about a man named Cyrus Eaton, a former Baptist minister turned savvy financier. Hailing from Ohio, Eaton had been in the utility business since the early 1900s, and, by the mid-1920s, had acquired two utility holding companies. Slowly and quietly, Eaton began buying up large portions of Insull’s Commonwealth Edison, Public Service, People’s Gas, and Middle West. In 1928, Insull was shocked to learn that Eaton’s portion of the pie was larger than his own. Insull had always kept an eye on the House of Morgan, but had never considered a local insurgent.

What did Eaton want? The man baffled Insull. Over and over again, Eaton relayed to Insull that he had no desire to control Insull’s empire; he just wanted a good return on capital invested. This rationale Insull could not understand. So, when Eaton offered Insull a sweet deal—Eaton would own, and Insull would operate exclusively—Insull didn’t trust it. He was an old dragon who preferred his hoard beneath him, whatever the cost.

Acting on his assumption that Eaton sought to take over his enterprises, Insull consolidated his entire empire into a single holding company: Insull Utility Investments. When IUI debuted on the stock market in January of 1929, it was worth $25 a share. In six months the frenzied market sent it to $150. At the same time, some of Insull’s subsidiary companies saw their stock double or better, which increased the prices IUI had to pay for those subsidiaries’ stock. To keep his financial grip on his empire, Insull formed an investment trust—the Corporation Securities Company of Chicago, or CORP—and then gave CORP and IUI partial ownership over each other. If Eaton wanted it, he’d have to buy it all. Insull felt well-fortified.

The Roaring Twenties closed with a smiling Insull featured for the third time on the cover of Time magazine. Months later, the stock market crashed. Insull met Black Friday—October 19, 1929—with hubris. “The stock market has not made the slightest difference to our policies,” he said. To prove it, he sank $200 million in capital-intensive projects, $80 million of which belonged to a natural gas pipeline that stretched from Texas to Chicago. He even advanced cash to his employees so that they could cover their brokerage accounts. Then, he enlisted his greatest ad man to promote an “everything is normal” campaign that would ease the public’s fears about Insull’s companies pulling their money out of the economy. This campaign, Insull explained at a December 1929 meeting of all the dons of the utility business, would mean going on the offense against pesky journalists, meddlesome politicians, and annoying citizens’ groups. A young man named Wendell Wilkie, who served as chief legal counsel for the largest utility in the South, Commonwealth & Southern, wondered aloud why the industry should have to take such an aggressive stance if their activities were all above board. “Mr. Wilkie,” Insull snarled, “when you are older, you will know more.” Wilkie would soon have to deal with the backlash against Insull’s tactics during the Great Depression.

Regardless, Insull’s companies saw their earnings jump by 15 percent in 1930. Power demand continued to rise as well despite the crash, which meant Insull had to keep expanding. In even better news, the crash made newly available vast sums of low-interest money. Insull went on a borrowing frenzy: $140 million in 1930. Securing such large loans without the need for New York financiers’ aid inspired a saber-rattling speech at the Chicago Stock Exchange. Insull called for a “war of financial liberation against Wall Street,” raising the ire of the money men already cankered by his insolence. Just a few years prior, Insull had acquired two enormous holding companies on the East Coast right under J.P. Morgan’s nose. These were men who commanded a fealty toward whom Insull refused to demonstrate, “and that made bad blood between them,” an industry insider reported at the time—“real bad blood.”

If Insull had marched East on horseback, he would return home in rags. His paranoia about Eaton persisted until he eventually bought Eaton out for $56 million at $350 a share, $40 above the market price. The lion’s share of the purchase came from money borrowed from his own companies, but $20 million of it had been secured from his enemies on Wall Street. The first half of 1931 delivered growth so robust, Insull was briefly rescued from his own appetite for risk: it vaporized his previous losses and brought his companies into alignment with their book value. Nevertheless, the kite string popped that September when England ditched the gold standard, lopping a third off the US stock market and $150 million off of Insull’s companies. From there, the beatings continued. Insull’s enemies in New York prosecuted a cutthroat campaign of rumor-mongering and subterfuge to nose dive Insull stocks, which spiraled downward to around $2 a share. The Wall Streeters then called in their debts. Insull’s recklessness had delivered his empire unto the hands of his foes.

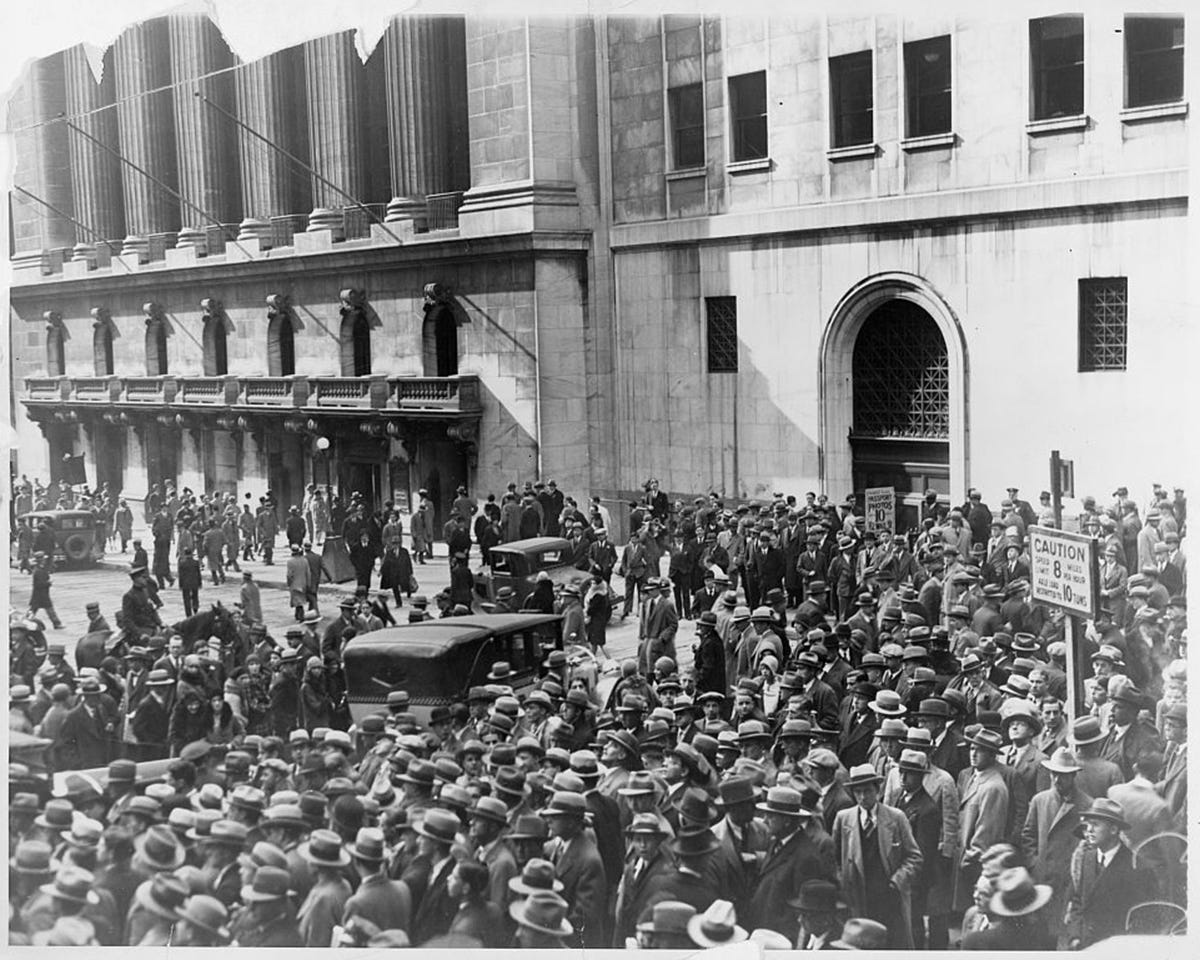

Morgan and his allies brought in the accounting firm Arthur Andersen & Co. to straighten out Insull’s books. What Andersen found shocked him: sketchy inter-corporate loans and tricky bookkeeping had been keeping Insull’s empire afloat. These revelations, when made public, guttered Insull’s reputation and retroactively bankrupted Middle West Utilities overnight. The New Yorkers delivered their final blow in the summer of 1932, when they forced Insull into receivership and then out of his own companies. Insull summed up the cataclysm tidily enough: “I—my companies—spent money as though things were alright. We increased our floating debt and this eventually brought about our bankruptcy.” Insull had lost public stockholders $600 million and wiped out the savings of some 600,000 people. The public felt bamboozled, suckered into investments they little understood (disclosure laws were not then what they are now) and over which they exerted no real control—all thanks to Insull’s unceasing barrage of advertising.

And it was at this precise moment of weakness that the Federal Trade Commission began to publish its findings on the behavior of the utility industry. Every month, the commission published excerpts from the 80 volumes of research it had completed, all of which teemed with seedy business dealings and corporate abuse. The report exposed NELA’s aggressive efforts to encourage utility boosterism, promote preferred stock purchases, and suppress criticism through its 25 million pieces of literature and countless radio broadcasts and speeches—all for which it had charged consumers. NELA’s campaign, in the estimation of the FTC, was the greatest propaganda effort that had “ever been conducted except possibly by governments in wartime.” Insull’s “ownership society” of non-voting common stockholders now looked like a scam. The revelations looked so bad that NELA had to change its name to the Edison Electric Institute to spare its reputation, promising to “divest itself of all semblance of propaganda activities” and “assume an attitude of frankness and ready cooperation in its dealings with the public.”

Progressives like George Norris took the opportunity to gain the high ground and went on the attack, aided by their new champion, former New York Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had ridden into the Oval Office by taking aim at the utility industry at large and Samuel Insull in particular. In the fall of 1932, FDR started sharpening his knives against Insull and the utility industry on the presidential campaign trail. While speaking in Portland, Oregon, FDR spelled out his desire for regional public power entities that would serve as “a national yardstick to prevent extortion against the public and to encourage the wider use of that servant of the people—electric power.” Roosevelt knew the industry would marshal the whole of its forces to stop him. He threw down the gauntlet. “To the people of this country I have but one answer on this subject. Judge me by the enemies I have made. Judge me by the selfish purposes of these utility leaders who have talked of radicalism while they were selling watered stock to the people and using our schools to deceive the coming generation.” The crowd roared.

Two days later in California, Roosevelt took direct aim at Insull, saying, “Whenever in the pursuit of this objective the lone wolf, the unethical competitor, the reckless promoter, the Ishmael or Insull whose hand is against every man's, declines to join in achieving an end recognized as being for the public welfare, and threatens to drag the industry back to a state of anarchy, the Government may properly be asked to apply restraint.” Roosevelt wanted Insull behind bars.

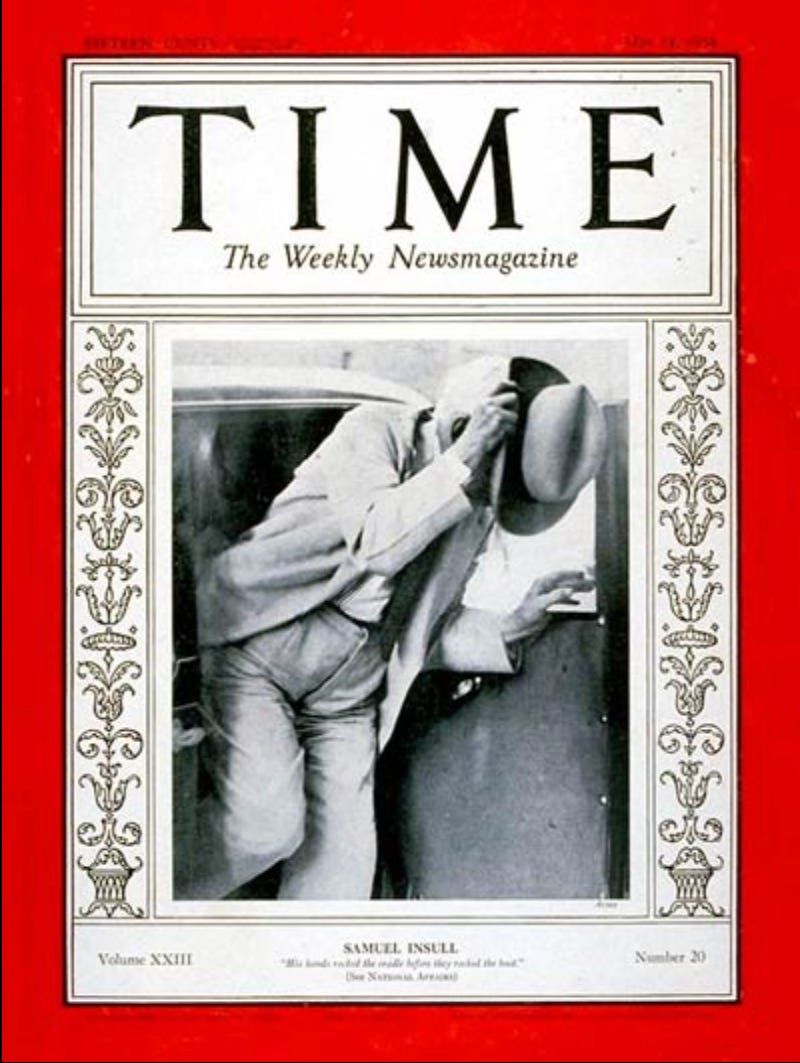

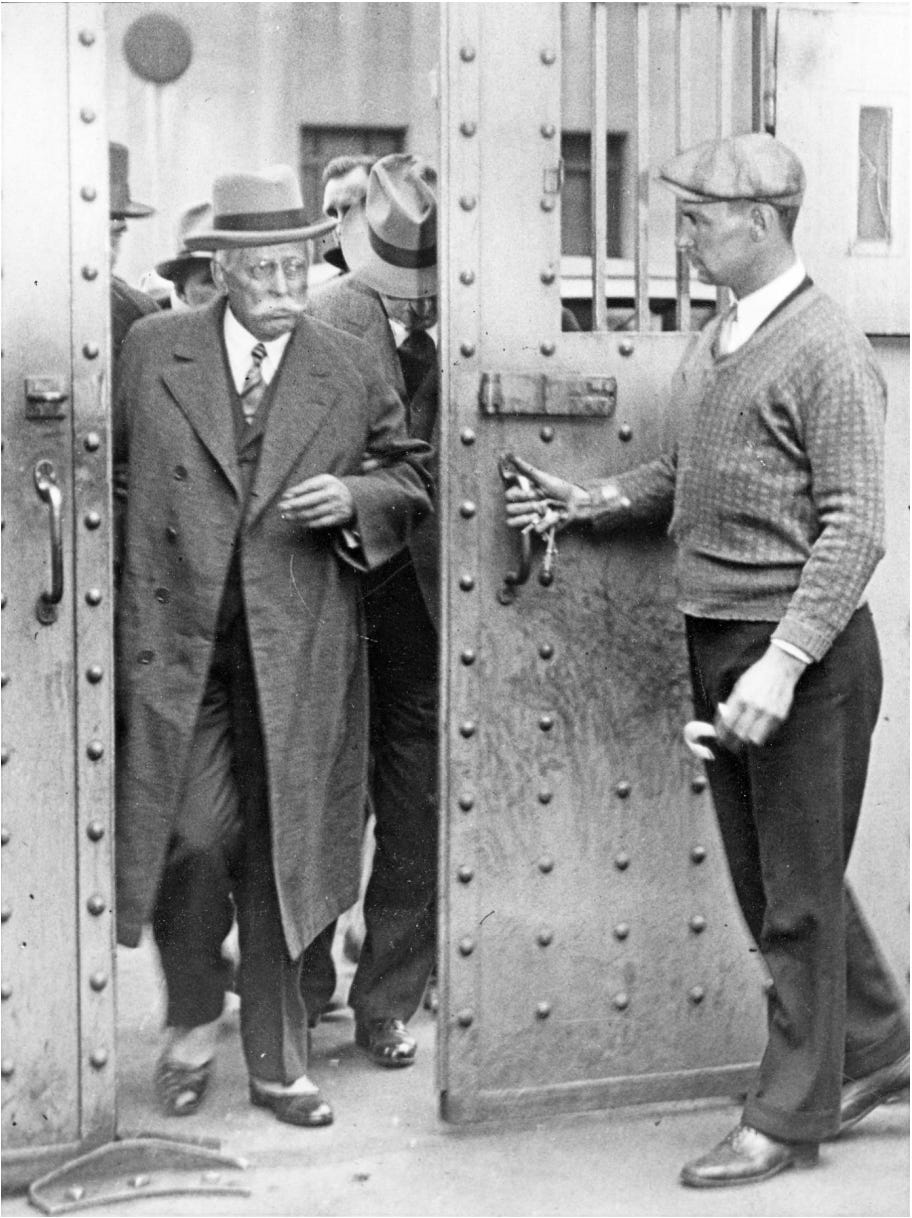

Insull got wind that he was wanted in court in Illinois. Seeing no reason to put his head in the lion’s mouth, as he put it, he fled to Paris. But Insull’s refuge in Europe couldn’t last. As soon as FDR took office, the president hounded the former utility kingpin throughout the Mediterranean, settling down in Greece. Finally, after threatening the Greek government with trade curtailments, Greek authorities surrendered Insull over to America in 1934. Roosevelt had personally signed the extradition request. Insull prepared his memoirs on the trip home. He earned a third cover of Time magazine that year, with his hat covering his face for shame as he clumsily exited his car on the way to court.

The jury set to decide Insull’s fate had a difficult time convicting him for fraud. The first obstacle was explaining the case, which involved complex financial structures in a cutting edge industry. Then there was Insull himself, by then fragile and aged, who came off as a kindly old man who had ridden to fame and success by virtue of his talents. In a fight between the prosecution’s emphasis on the nefarious latticework of holding company ownership structures and the defense’s retreat to the redoubt of Insull’s character, the man won. Besides, if he had been a conman, then he hadn’t been any good at it. Insull had done everything in his power to rescue his companies from bankruptcy, including bankrupting himself. The jury came back with its verdict: not guilty.

Insull booked a trip back to France to live out his remaining years. “If modesty permits, I would say that it has been my privilege […] to make some contributions toward the economic success” of the power industry, Insull wrote in his memoirs. “What those contributions really amount to must be left to posterity to decide if they should seem to the future students of these industries of sufficient consequence to claim attention.” This could only be false modesty. Insull had led his industry out of the desert of limited adoption and into the promised land of a mass consumer society that thrived on kilowatt-hours. He had created the regulatory compact that would hold for over a century, and his build-and-grow strategy would serve as the industry standard until the 1970s. Insull gave the whole of his life to his gospel of electric growth, and the country benefited greatly from hearing the good word. And yet, in 1938, Samuel Insull died alone at the age of 78 after his heart gave out on the Paris subway. He had 85 cents in his pocket. Seventeen mourners attended his funeral, with no family members among them. Papers circulated word of his death, portraying him as a failure.

Yet at that very moment, one of Roosevelt’s champions, a Hoosier lawyer named David Lilienthal, was proving Insull right all over again on the government’s behalf in the Tennessee Valley. But that’s a story for another time.

Bibliography

Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (New York, NY: Library of America, 1983).

Mark Aldrich, The Rise and Fall of King Coal: American Energy Transitions in an Age of Markets, 1800 - 1940 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2025).

Dr. Frederick H. Bates, “‘Old Elmhurst: Being the Personal Recollections of a Native,’” Elmhurst Historical Commission, 1973.

Helmut Alan Berens, Elmhurst: Prairie to Tree Town (Elmhurst, IL: Elmhurst Historical Commission, 1968).

Robert Bryce, A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations (New York, NY: Public Affairs, 2020).

William D. Cohan, Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon (New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2022).

Julie A. Cohn, The Grid: Biography of an American Technology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017).

Herbert Croly, The Promise of American Life (New York, NY: MacMillan, 1912).

William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991).

Edwin T. Layton, Jr., The Revolt of the Engineers: Social Responsibility and the American Engineering Profession (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986).

Lynn Dumenil, The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1995).

Robert Faulkner, The Case for Greatness: Honorable Ambition and Its Critics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007).

Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920 (Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh University Press, 1999).

Richard F. Hirsh, Power Loss: The Origins of Deregulation and Restructuring in the American Electric Utility System (Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press, 1999).

Richard F. Hirsh, Technology and Transformation in the American Electric Utility Industry (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

John Hogan, A Spirit Capable: The Story of Commonwealth Edison (Chicago, IL: Mobium Press, 1986).

Thomas P. Hughes, American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 204-205.

Samuel Insull, The Memoirs of Samuel Insull (Polo, IL: Transportation Trails, 1992).

Samuel Insull, Public Utilities in Modern Life: Selected Speeches (1914-1923) (Chicago, IL: Privately Printed, 1924).

Jill Jonnes, Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World (New York, NY: Random House, 2003).

Jeremiah D. Lambert, Power Brokers: The Struggle to Shape and Control the Electric Power Industry (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2015).

Jon K. Lauck, The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800 - 1900 (Norman, OK: Oklahoma University Press, 2022).

T.J. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880 - 1920 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1981).

Jackson Lears, Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877-1920 (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 2009).

David Levering Lewis, The Improbable Wendell Wilkie: The Businessman Who Saved the Republican Party and His Country, and Conceived a New World Order (New York, NY: Liveright, 2018).

John Marini, Unmasking the Administrative State: The Crisis of American Politics in the Twenty-First Century (New York, NY: Encounter Books, 2019).

Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Thomas K. McCraw, TVA and the Power Fight, 1933 - 1939 (Philadelphia, PA: J.P. Lippingcott Company, 1971).

Forrest McDonald, Insull: The Rise and Fall of a Billionaire Utility Tycoon (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

Richard Munson, From Edison to Enron: The Business of Power and What It Means for the Future of Electricity (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2005).

John L. Neufeld, Selling Power: Economics, Policy, and Electric Utilities Before 1940 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

David E. Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880 - 1940 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001).

Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021).

Harold L. Platt, The Electric City: Energy and the Growth of the Chicago Area, 1880-1930 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

Terry S. Reynolds ed., The Engineer in America: A Historical Anthology from Technology and Culture (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

John A. Riggs, High Tension: FDR’s Battle to Power America (New York, NY: Diversion Books, 2020).

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Campaign Address in Portland, Oregon on Public Utilities and Development of Hydro-Electric Power,” September 21, 1932.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Speech in San Francisco,” September 23, 1932.

Jeffrey L. Rodengen, Sargent & Lundy: Thinking Power…Exclusively (Fort Lauderdale, FL: Write Stuff, 2017).

Don Russell, Elmhurst: Trails from Yesterday (Elmhurst, IL: Heritage Committee of the Elmhurst Bicentennial Commission, 1977).

Sandeep Vaheesan, Democracy in Power: A History of Electrification in the United States (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2024).

John F. Wasik, Merchant of Power: Sam Insull, Thomas Edison, and the Creation of the Modern Metropolis (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

Daniel L. Wuebben, Power-Lined: Electricity, Landscape, and the American Mind (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2019).

Such a great series, thank you for writing and sharing it. Knowing what happened with Enron much later, the fact that it was Arthur Andersen the firm that inspected Insull's businesses and found accounting problems, leading to the downfall of what was then the largest power company, is one of those touches of irony that only history can deliver.