Samuel Insull: The Father of Light Pt. III

It's Good to Be King

Before you dive in, check out Part I and Part II of this series!

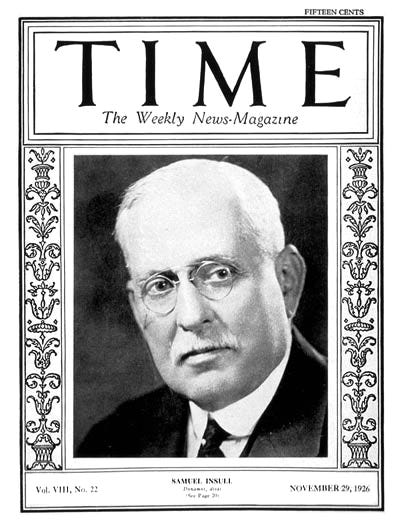

In the mid-17th century, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote his magnum opus, Leviathan, in which he argues for a social contract between subjects to exit the violent state of nature by agreeing to give over the whole of their power to an omnipotent king. In the frontispiece of the book, an enormous king in a chainmail shirt gazes down on his lands. A discerning eye would notice that the chainmail shirt is actually a web of men; his body, and thus his authority, derive from the power his subjects vest in him. Insull, like Hobbes’s king, looked down upon a map of America; what appeared as a business suit would, on closer inspection, reveal itself as a weave of plant workers, customers, politicians, power lines, turbogenerators, coal mines, railroads, and regulatory statutes. His empire spread across the country, touching both coasts, and would grow north of 10 percent of America’s total electricity output. In scope and scale he was peerless. He stood as a Napoleon electric, industrial history on horseback, remaking American society in his image. And he did so with an astounding level of public consent.

None could deny electricity’s positive impact on everyday life, which grew more electrified by the day. Before electrification, women scalded themselves on hot irons heated in ovens, worked their hands to the bone sweeping and beating rugs, and hauled cold water into the home to be heated for laundry and bathing. Inventions like the electric iron, the electric vacuum, and electrified water heating systems shrank the drudgery and time these tasks required by orders of magnitude.

Electrification also raised hygienic standards by making it easier and more affordable for people to bathe or wash their clothes multiple times a week. For children, electric lighting improved educational opportunities. Electrified schools made reading easier, while at home, where gas systems proved dangerous to leave in a child’s control, electric lights made for a safer, easier-on-the-eyes option, further facilitating more reading. As Muncie, Indiana electrified, its library “loaned out eight times more books per inhabitant in 1925 than 1890.”

These changes were so palpable, utility ad copy from this period reads more like plain statements of fact than exaggerated PR. Insull’s Commonwealth Edison, for example, boasted, “For the modern household, Electricity is at once a servant, a source of heat and light and unfailing convenience that can be enjoyed every day in the year. In any house that is wired for Electric Light, these modern labor savers will be appreciated.” Electric appliances nearly sold themselves, though that didn’t stop the National Electric Light Association from pushing goods on every customer it could. Between 1915 and 1920, electrical appliance sales skyrocketed from $23 million to $83 million. In 1923, 75 to 85 percent of Chicago residents lit their homes with Insull’s currents. By 1926, 82.5 percent of Chicagoans used electric irons, 71 percent ran electric vacuums over their carpets, and over 30 percent of utility customers made breakfast with toasters and washed their clothes in electric washers.

Electrification also alleviated the sewage and horse-traffic congestion problems that had choked major cities like Chicago. Insull, with his commitment to electrified public transit, had been a prime mover in solving these issues; he consolidated and expanded the city’s transit system all the way out to Indiana. His domination meant increased scale, better management, cheaper fares, and overall rationalization. Electrified transit also helped solve the puzzle of spreading power load throughout the day. In 1893, dazzled Chicagoans rode an electric rail around the White City, cruised through the fair’s canals on battery-powered gondolas, and witnessed the wonders of a futuristic electrified home. It was a dream city that Insull had made real.

Electricity remodeled American home life, civic life, and work life in ways unimagined, inspiring a thrilling sense of vertigo as the nation scaled the snow-dusted peaks of technological improvement. Though technical knowledge of electricity was scarce among the general public, the people reckoned that this mysterious power source brought with it a bounty as common as it was novel. In a way, Henry Adams had been right in his reflections at the 1893 World’s Fair. While technological progress and massive economic development provoked great anxiety in some, by and large these changes were greeted with open arms. “Before long,” Adams had prophesied, “one began to pray to [the dynamo]; inherited instinct taught the natural expression of man before silent and infinite force.” He could sense “an absolute fiat in electricity” similar to religious faith.

Insull was one of the main beneficiaries of this new religious faith in applied science. If electricity meant a bountiful future of dizzying potential, Insull was the electricity industry’s face, its Leviathan, who received almost unmitigated control in exchange for the material fruits of progress.

But not everyone loved Insull or the utility industry, whatever their positive impact on the lives of Americans. A man doesn’t rise to Insull’s heights without making enemies, and his enemies spent the 1920s lying in wait. On one side stood the Wall Streeters such as J.P. Morgan, who resented that Insull managed to finance his entire enterprise without ever once coming to them for money. Thus his rise benefited them not at all, and they liked that about as much as they did his defiance. Every other industry titan genuflected before the kings of New York’s banking institutions, but not Insull. He had never forgotten what Morgan had done to Thomas Edison. On the other side stood a more radical band of Progressives, still clinging to their old faith in government intervention, who believed that the entire power industry should be a publicly owned utility. They saw the rise of Insull as auguring a new technological tyranny that threatened to capture the government. Their politics were out of season during the Roaring Twenties, but their moment would come soon enough.

Insull himself seemed blissfully unconcerned about his offstage enemies as they sharpened their knives. His wife Gladys had better instincts about such potentialities than he. An accomplished actress and autodidact in her own right, Gladys had become obsessed with the figure of Napoleon. After reading a series of biographies on his character and exploits, she noticed an uncanny similarity between the Corsican nobody who ascended to the throne of the French Empire and her ambitious husband. “Sam, you should learn about that man, and about what happened to him. If you don’t,” she repeatedly warned, “that’s what’s going to happen to you.” Insull brushed her warnings off as trouble brewed about him.

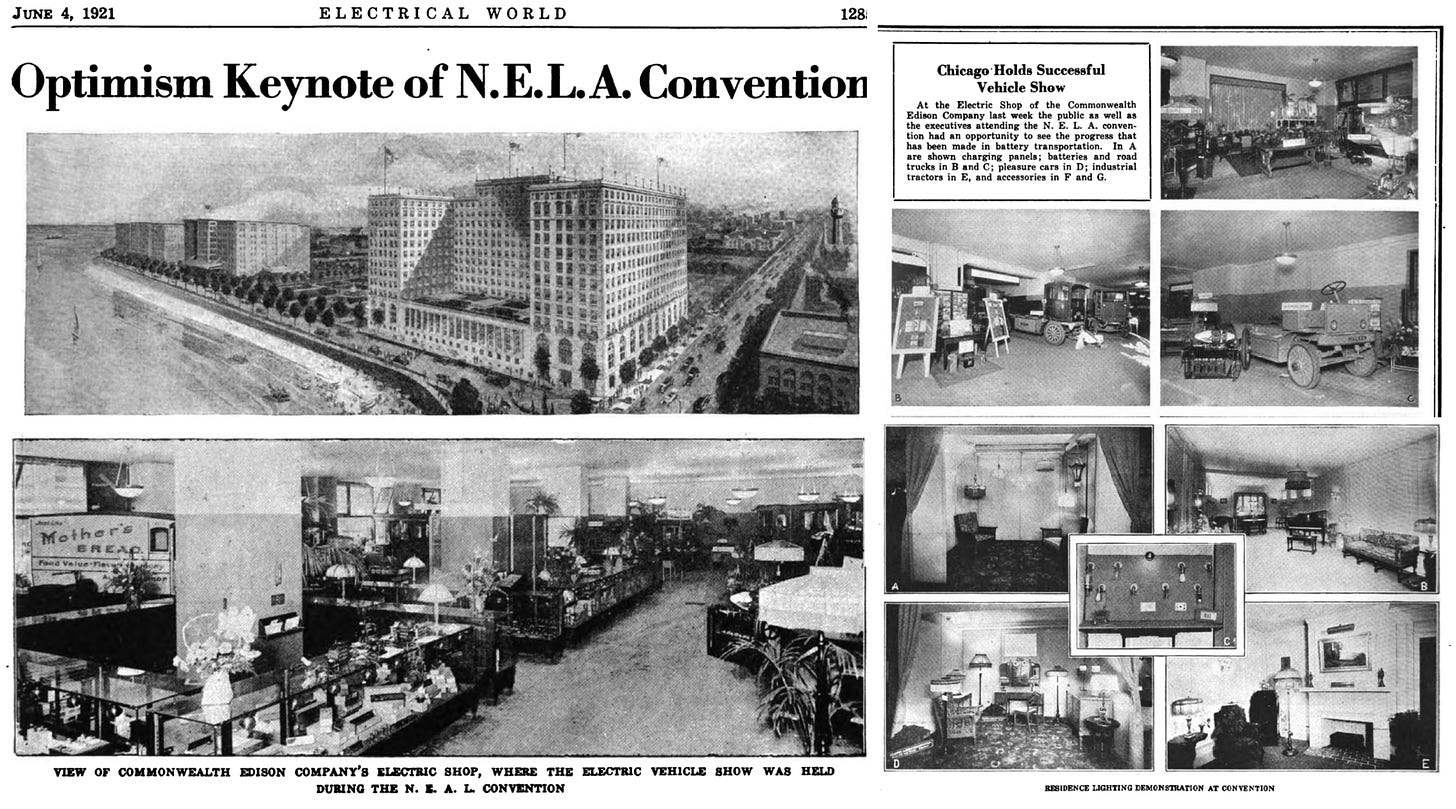

Meanwhile, Insull took his lessons from his war bond campaigns and applied them to the National Electric Light Association’s operations. In 1921, NELA’s national publicity-coordinating committee loosed a torrent of pro-utility propaganda: subsidizing teachers, reports, and school officials; putting on radio, church, club, school, and college programs hosted by utility spokesmen; ghost-writing news bulletins, editorials bylined by prominent citizens, pamphlets, textbooks, law reports, and circulars. NELA pursued every means of publicity, NELA’s publicity director remarked, “except skywriting.” Much of their material was disguised as objective evaluations from disinterested third parties. In Illinois, 75 percent of high schools used “industry-supported materials in their classrooms.”

In addition to the more anodyne, self-aggrandizing industry boosterism, NELA’s national campaign focused on discouraging the public from pursuing municipal or public power strategies (deemed “socialistic”) along with any strengthening of the regulatory regime. They believed their own efforts a great success in this regard. One NELA member noted, “We’d all be in a hell of a shape…Without this, I venture to say that State, municipal, and Government ownership would have been 100 percent ahead of what it is today.” When it came to NELA’s strategy, Insull presented a Janus face. On one side, he cautioned the national publicity committee against being too “one-sided” lest they be accused of propagandizing or molding public opinion. On the other side, Insull said, “The public is in no position to judge service and rates when it knows nothing about the multitude of details involved in furnishing service.”

None of these sometimes-multi-million dollar campaigns came cheap for customers. Utilities, both independently and through NELA, simply charged publicity expenses as operating costs, recouped by increasing customers’ bills. NELA’s managing director put it bluntly: “Don’t be afraid of the expense; the public pays the bills.” Such a credo cut against the cult of “service” upon which the industry had premised its good name; however, the public wasn’t aware that any of this was going on, and, moreover, rates stayed low. But where NELA made its worst misstep, and Insull with it, was in its ceaseless “customer ownership” campaigns that encouraged the acquisition of non-voting shares of utility stock (also known as “preferred stock”). Insull and his colleagues in the industry charged customers for propaganda that encouraged them to invest in the utility system—essentially, taking their money twice over.

To Insull, preferred stock served several purposes simultaneously. The country wanted more electrification, and everyone knew the utility industry was growing at a breakneck pace. Offering non-voting shares to customers let the public get in on the action, and the stock was both marketed and perceived as a kind of wealth redistribution through ownership. Customer ownership had a rhetorical genius to it. This tack catered to American cultural preferences for individual over public ownership and wedded well to the stock-crazed zeitgeist of the Jazz Age.

All of Insull’s stocks were listed on the New York Stock Exchange, and everyone from blue-collar factory workers to big Chicago bankers saw Insull as an infallible genius with a Midas touch for business. Everyone wanted a piece of the action. “If we issued a piece of brown paper with a signature on it, we could raise all the money we wanted to,” Insull said, looking back on the Twenties. He grew rich along with his stock-owners, however mean their station, and it was this aspect that built a political wall around utilities, protecting them from any attacks. Insull wasn’t a greedy fat cat, many thought, because he was offering the little guy a way to get ahead. And because so many people from so many walks of life owned utility stock, they looked askance at political attempts to interfere with their investments. Would-be “hostile voters” blossomed into “utility stakeholders.” These two factors sufficed for Insull to insist that customer ownership was vital to the industry’s long-term success.

But common stock’s most vital function for Insull, and for the industry at large, solved a major difficulty in the utility industry’s growth. By the 1920s, the utility industry was no longer a local game. As power lines attempted to cross into different states to secure greater efficiency and economies of scale, it became increasingly difficult for legal teams and engineers to navigate the patchwork of legal and technical variables between states. This also posed a problem for investors. Though state regulation had de-risked utility investment to a large degree, cautious bankers hesitated to loan out money to regional system expansion projects liable to run into confusing regulatory challenges. Various government planning strategies meant to resolve these problems failed. Insull’s solution, the public utility holding company, elegantly weaved in between these obstacles and created a path forward for the industry.

A public utility holding company was a financial construct never before seen in America. Technically, it neither produced electricity nor served customers; “it controlled operating utilities that played that role,” yet there was “no clear threshold of the proportion of a company’s voting stock required for control or influence.” Thus, with less than $30 million invested, Insull could control over half a billion dollars in assets as well as most of the voting power. With a holding company, a utility could consolidate smaller, regional power and light companies under its control, which allowed holding companies to expand while skirting state regulation. For instance, a utility holding company headquartered in Illinois could own and operate a power and light company in Michigan, remaining answerable only to the Illinois state regulator. Holding companies sat at the top of pyramidal ownership structures—they were made from and controlled smaller companies. Holding companies thrived on preferred stock because it allowed utility companies to source capital and stabilize investments without having to respond to the wants and desires of preferred stock owners; their shares were non-voting.

The holding company strategy seemed to please everyone at once: utilities could grow without interference from stockowners or regulators; everyday people could get a financial leg up through wise investments in what were seen as stable companies with limitless potential; Insull himself could secure more capital without having to make a pilgrimage to New York. Predictably, common stock drove a second boom in the expansion of Insull’s domain. By the mid-1920s, Insull’s Middle West Utilities doubled in both size and sales, spreading its system into a third of the United States. In 1922, Commonwealth Edison was worth around $119 a share, but by 1929, the share price had leapt to $450. By mid-decade, utility bonds had grown into a billion-dollar-a-year-corner of the market. Insull could do no wrong, or so it appeared.

Love this series! Such an important topic.

Ohh, nice foreshadowing at the end there…