Samuel Insull: The Father of Light Pt. I

Edison's Heir Apparent

The great-souled man, who seeks a place worthy of his superiority, is not only generally unwelcome but also justly unwelcome and justly gotten rid of, at least according to a certain political justice.

—Robert Faulkner

Longtime subscribers know that I’ve been warning about American grid fragility for years. We’re short on spare capacity and long on increasing demand: a recipe for disaster. As we navigate these challenging waters, I think we should reflect on how the grid got built, who built it, and how they did it.

One man stands above all the others in our national annals—Samuel Insull. If you haven’t heard of him, don’t worry. This is the first in a several part series dedicated to telling the story of his achievements. At the end of the series, I’ll provide a bibliography of all the research material I used.

I’d like to thank the staff at the Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center who helped me find rare material published by Insull. I would also like to thank Daniel Lund, the Curator of Collections at the Elmhurst History Museum, who allowed me to see the historical documents concerning my home town’s experience with early electrification. Robert Bryce as well as Madi and Griffin Hilly provided invaluable feedback on earlier, more laborious drafts of this series. This series would be greatly impoverished without their insight. John Goodson, Canada Mike, and the Electricity Degenerates (you know who you are) offered crucial moral support during the laborious research process. I am also indebted to the editorial assistance of both my colleague at Foundation for American Innovation, Robert Bellafiore, and my patient and lovely wife.

What was Samuel Insull thinking? He was just 21 years old, and yet here he was explaining to his family and friends that he was about to move from England to America with no job lined up. But he had seen the future: electricity. Most of the world still lit the night only by fire—wood, lumps of coal, peat, whale oil. Electric power was mostly a luxury product with few uses, and yet Insull knew that it could change everything about humanity's future. And he knew that in order to lead that future, he had to work for Thomas Edison.

Insull had gotten his start working for the man at his London telephone company. Insull spent his days memorizing the contracts of every single one of Edison’s business contracts and his off hours hounding engineers to understand the technical in and outs of electricity. As a reward for his efforts, Insull was offered the opportunity to become Mr. Edison’s secretary. The details of such a position were not forthcoming—he’d have to move to America to discover what lay in store. With the unshakeable confidence in himself, appetite for risk, and feverish ambition that would carry him from office boy to the emperor of the America power system, Insull shrugged off his family’s warnings. In February of 1881, he boarded a ship bound for New York.

Upon stepping onto the pier in New York, Insull walked straight to Edison’s office. When they met, Insull and Edison discovered that they couldn’t understand what the other was saying. Edison's Ohio twang puzzled Insull; Insull's cockney brogue baffled Edison. Once they surmounted the “language barrier,” Edison explained that he needed Insull's help with something big: he wanted to ditch his European telephone businesses and commit himself in full to electric light, but he didn’t know how to go about it. He didn’t even know how his European businesses were structured. So Insull commenced to walk Edison through the exact nature of his European contracts in detail from memory into the wee hours of the morning. By the end of their first hours together—Insull's first hours in America—he had won his hero's confidence. Edison could now ditch his European interests and home in on a new American task: conquering darkness. After a few hours of sleep, Insull woke up to begin his "next day" of work, shepherding America into the Electric Age.

Over the course of the 1880s, Insull rose through the ranks at Edison General Electric. As the one man who could keep up with Edison’s grueling work pace, Insull established himself as the wizard’s perfect business partner. Their skills complemented each other: Insull could masterfully organize the businesses that spooled out of Edison’s quest to found the kingdom of electricity. Insull performed so well, he was soon tasked with running Edison’s utility business, where he traveled the country selling municipalities on the total Edison light system—power plants, transmission lines, and lamps. By the end of the decade, he had risen to the role of chief financial advisor and gained Edison’s power of attorney.

But even with Insull’s help, Edison's dream of an electrified America was not to be achieved by his own hand. His ego locked him out of his own destiny. By the end of the 1880s, Edison’s business model was failing. His major advance in electric power had been the direct current system. In such a system, a power generator pushed electrons along an expensive copper wire toward their destination. But the farther they traveled, the weaker they got, in a phenomenon called “line loss.” Because the uniform voltage of the power fatigued against resistance from the copper wire, if Edison wanted to serve more customers, he had to build more power plants and string up more copper wire. Even worse, he had to over-build to match supply and demand. If a lamp needed 80 volts of power, then the power plants had to crank out 90 volts of power to account for line loss. This made scaling up the power system more expensive for both Edison and his customers because it confined each power plant’s service area to a one-mile radius. Unfortunately for Edison, a man named George Westinghouse would disrupt the inventor’s entire business model.

Unlike Edison, Westinghouse recognized the economic shortcoming of direct current. He solved the problem by putting alternating current—a more powerful, though up until then, more dangerous form of electricity. Westinghouse’s company had developed something called a transformer, which allowed the voltage of electricity to be “stepped up” or stepped down.” In other words, in order to deliver power to that 80 volt lamp, Westinghouse could use a transformer to increase the voltage of power, thus moving it over a long stretch of line with less line loss, and then decrease that voltage to the exact amount the lamp needed. Using transformers to tame and manipulate alternating current allowed Westinghouse to serve more customers per power line and power plant over a larger geography. This meant capital costs for an AC system were lower; for Edison’s DC systems, the opposite was true.

And yet Edison clung to his DC system out of a stubborn amalgam of ego and spite. Who were these upstarts to challenge his dominion over the industry he had brought forth by the sweat of his brow? But the economics and the physics proved inexorable. DC was vastly inferior to AC; Edison’s empire slipped from his fingers. Insull didn’t share his master’s recalcitrance. He respected Westinghouse and, in hindsight, viewed the whole rivalry as “very ridiculous.”

Like Insull, the banking magnate J.P. Morgan, one of Edison's main financiers, saw clearly what Edison could not: Edison’s empire needed to be saved from its founder. In 1892, Morgan consolidated Edison General Electric with one of its competitors, Thomson-Houston, and renamed the company General Electric, stripping the great inventor’s name from the company he had founded. The birth of GE sounded the death knell of Edison’s role in the electricity industry.

Insull recognized that Edison’s untenable stance on AC had made his job of financing the company impossible, but to remove Edison’s name galled him; Morgan’s ruthlessness forever soured Insull on the New York banking set. In the aftermath, Insull found himself in a high-paying VP spot at GE, but with no route to the Olympian heights he sought. He had gotten a taste of greatness with Edison and his appetite for more had grown ravenous. Playing second fiddle at GE held no interest for him. Moreover, he didn't want to deal with any New York bankers like Morgan. Out of a sense of duty, he hung on at GE for a year to ease the transition, all the while contemplating his next move.

Opportunity blew in from the Windy City. Chicago Edison was putting feelers out for a new president and wanted to know if Insull was interested. At the time, Chicago was growing into one of America's largest cities. By virtue of its status as the “gateway to the West” through railroad connections and its burgeoning commodities market, Chicago had turned into one enormous boomtown. Chicago Edison needed an ambitious president to help the utility keep up with its host city. Was Insull interested? On the one hand, to take the position would mean a substantial pay cut and an equal reduction in prestige. On the other hand, hidden in this demotion lay an opportunity only Insull had eyes keen enough to see.

In his time as Edison’s second in command, Insull had become convinced that the utility business, not manufacturing, was the electricity sector's future. Sure, demand for power stations, electric traction, lightbulbs and all the rest would grow, but that also spelled vast growth in the demand for power itself. Just as he had risked it all to join Edison in America, Insull bet on himself as the man who would shape the world to come. He accepted the leadership position and became the firm’s president in July of 1892, a few months after GE officially incorporated in New York. It required a 66 percent pay cut, but Insull was “not looking to the amount of [his] remuneration” as he put it. He was looking at the size of the opportunity.

To celebrate his departure to the Midwest, Insull threw a dinner party at swank restaurant in New York. All the luminaries of the industry, including the leadership of GE, dined, drank, chattered, and joked until Insull stood up to speak and brought a hush to the room. Toasting himself, he forecasted that “[e]ventually Chicago Edison will probably equal or exceed the investment of the General Electric Company.” The prediction was hubristic, if not ridiculous: General Electric owned a large slice of the manufacturing oligopoly pie; Chicago Edison was a local utility sunk into a polluted American backwater. Yet no one dared laugh at Insull’s moxie, because they recognized the look in his eye when he spoke. Time would reveal that Insull belonged not to his guests' future, but they to his. He awoke the next morning and headed West, where he would pluck Edison’s crown from the gutter and place it upon his own head. Insull was thirty-two.

The year after Insull arrived, Chicago hosted the 1893 World’s Fair. Lit entirely by George Westinghouse, it was there that Americans bore witness to the glories that the electric dynamo brought to the world. Fairgoers could putter around in electric gondolas or ride the towering electric-power Ferris Wheel and survey all of Chicago, glittering in the night like a diamond. The White City, as the fairgrounds were called, stood on two square miles and contained 10 percent of the nation’s artificial light at the time. While Paris’s World’s Fair in 1889 had used 1,150 arc lights, 10,000 incandescent lamps, and generated a total of 3,000 horsepower, Chicago’s boasted 10 times more light and horsepower. The White City showed the country, which still lived in an agrarian mode, what an industrialized, urban future held for them—a future as incredible as it was near.

Henry Adams, grandson to former president John Quincy Adams, and great-grandson to founding father John Adams, ambled around the White City, dizzied with awe. As he made his way through the fair grounds, he found himself at the Electricity Building. He marveled at the whirring dynamos—what we now call power generators—within. Over the next few weeks, Adams would return again and again to these mechanical beasts of burden which set the White City aglow. What about these industrial wonders transfixed him? The dynamo represented an “abyssal fracture for a historian’s objects.” A new world was being born—rationalistic, capitalistic, mechanistic—and with it, a new, and thus unknown, America. “Chicago asked in 1893 for the first time the question whether the American people knew where they were driving,” wrote Adams. Insull seemed like one of the few men who truly knew.

Yet despite all this fanfare, not many in the power industry had high hopes for their future in the city. After the fair, a nation-wide economic depression settled in. On top of that, no one in the industry had yet discovered how to make decent money off electric power. Rate-making for customers was done by guesswork and approximation. With their capital costs high, margins slim, and opportunities thinning, a defeatist attitude overtook the young electricity business. With about 5,000 existing power customers, no one believed the ceiling for electric power users in Chicago sat higher than roughly 25,000. No one, that is, except Insull. He vowed to serve the whole city, whose growing population would add over a million residents by 1910.

The first hurdle to clear was cost. How could Insull take electricity—something only big city governments or the wealthy elite could afford—and turn it into something for everyday people? To do that, Insull would have to drive the price of power down below that of gas. Insull figured that to make power cheap, he had to make it abundant. And so he started to commission larger and larger power plants. Years before Henry Ford (who got his start working in an Edison utility) coined the phrase “mass production,” Insull called this approach the “massing of production,” driving down rates with bigger plants and more power output. To mass this production, Insull committed Chicago Edison to building the largest power plants in the world.

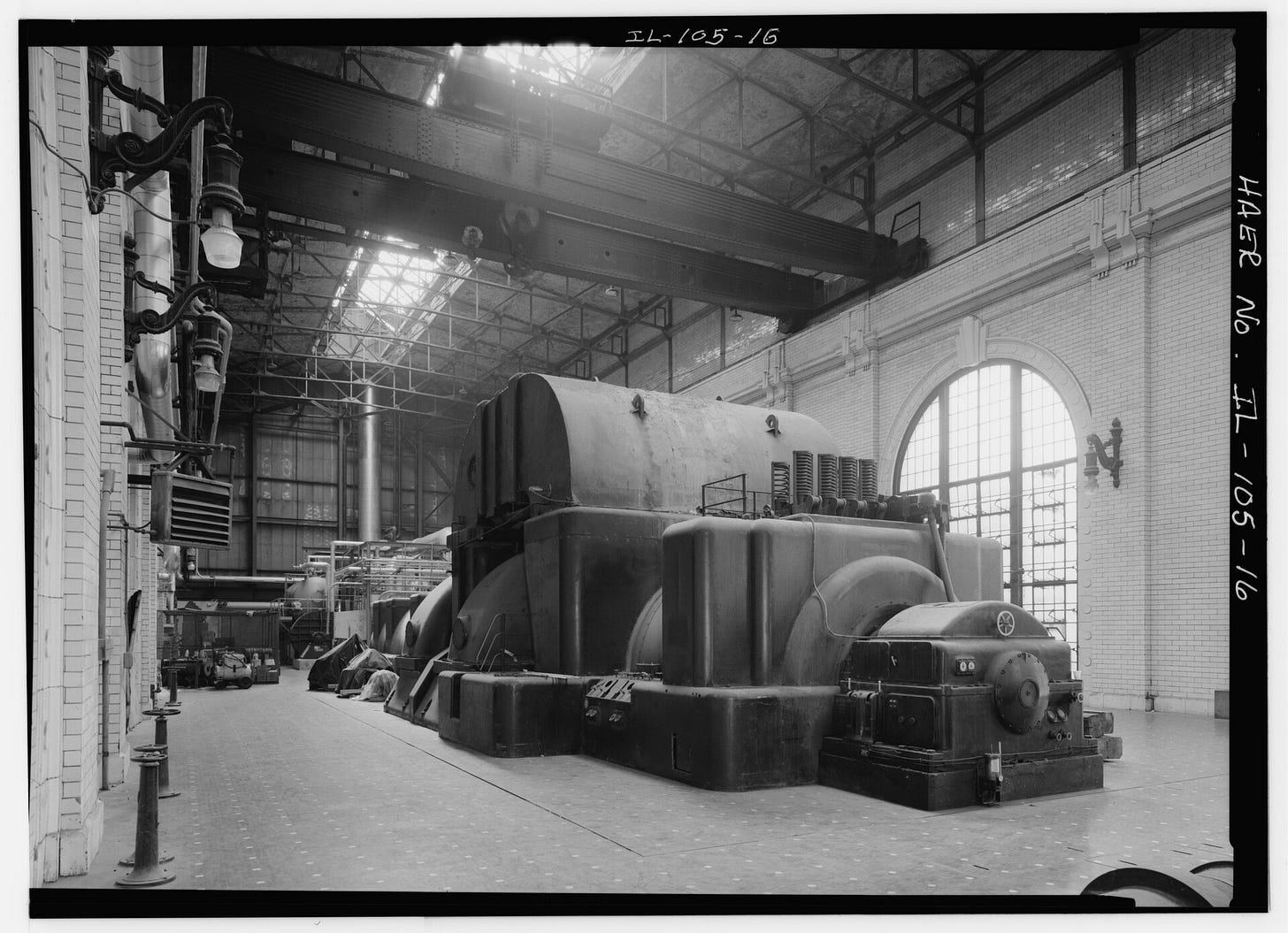

Insull pushed the envelope, routinely goading the engineers at General Electric to build power plants sometimes four times as large as any in existence. The construction of these reciprocating engines became too burdensome, with parts so large they could barely be moved let alone installed, and, once in operation, became so loud, smoky, and seismic in their motions that neighbors complained. Moreover, their efficiency topped once they grew to about 5,000 kilowatts of power output. The solution to this problem had been developed by British inventor Charles Parsons in 1884, when he created the turbine engine. While the reciprocating engine relied on cyclical motion (the up-and-down firing of a piston), Parsons’s turbine piped in high-pressure steam to spin a bladed shaft like a pinwheel, which was connected to a generator. This doubled the efficiency of power plants’ heat and motion to electricity conversion.

In 1901, on a European vacation, Insull discovered Parsons’s turbines and returned to Chicago envious. He wanted those turbines for himself, only larger, and began to pressure General Electric to build the biggest turbine in the world. General Electric, still new to turbine technology, doubted that it could fashion a regular-sized turbine, let alone one as big as Insull demanded. Insull wore them down. The company relented, on one condition: if GE was going to take all the manufacturing risk for this experimental 5,000 kW turbine, then Insull had to take on all the operating risks. We’ll build it, they said, but you deal with the consequences. At once, Insull commissioned Frederick Sargent, Chicago Edison’s consulting engineer, to design the largest power station America had ever seen to house the turbine. Insull felt that time was of the essence. “The opportunity to get this large power business was right at my threshold,” he wrote in his memoirs, “and I knew that unless I built the most economical power station possible, that opportunity would be lost.”

Chicago Edison built Sargent’s power station at Fisk Street in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. Once GE installed the 5,000 kW turbine (the largest generator GE had built up to that point was 600 kW) in 1903, Sargent hesitated before flipping the switch. He turned to Insull and asked him to quit the building. The engineer worried that the whole thing might explode when he flipped the switch.

Insull resolved to stay. “If you are to be blown up, I would prefer to be blown up with you as, if the turbine should fail, I should be blown up anyway,” he told Sargent. Insull had bet it all on this technology; there was no backing out now.

The Fisk turbine jolted awake—and then purred. Success. Insull ordered two more units just like it immediately, then another in 1905, and then had them all replaced in 1911 with even larger 12,000 kW units. Insull’s effort at Fisk Street would morph into an official strategy that would eventually be dubbed “grow-and-build”: fattening demand through customer diversity and territorial expansion, which then secured more profits to be reinvested in larger power generators, which then allowed for huge rate cuts, which then circled back around to bring previously priced out customers into the fold—rinse, repeat. The “grow-and-build” method would go on to govern the entire utility industry's entire business model up until the 1970s.

But it was no use to provide all of this cheap, efficient power if Insull wasn’t getting paid for it. All those hulking power plants cost a lot of money. Unfortunately, Insull had no way to charge people for exactly the amount of power they used. The imprecision meant that his power plants ran at one sixth of their full potential; all that physical capital other idled without making money. Temperamentally, Insull loathed operating on such shaky premises. He craved precision and control—financially and emotionally.

The solution finally came to him on another vacation to Brighton Beach back in England. Strolling the boardwalk, Insull smiled to see the storefronts lit with electric lights, which had won even such hard customers as modest shops. How could these shops afford it? Then a dial housed in a glass shell caught his eye; it ticked away, precisely logging power usage. It was the world’s first power usage meter, like the kind that stick out on the sides of homes and apartment buildings today. Insull promptly tracked down the man who invented these newfangled meters and inked a licensing deal with Chicago Edison. Now he could create different rates for different customers: large users received discounts, while small users paid more—and each paid only for the power they used. A greater diversity of customers would mean a greater diversity of load patterns, because not all customers peaked their power consumption at the same time. Spreading out peak usage across the day disincentivized overbuilding power systems, while maximizing cash flow. Power plants would no longer sit idle, bleeding cash.

With hulking power plants and low, accurate rates, Insull was well on his way to dominating the power business in Chicago. To fully capture the city, he needed a monopoly, which he pursued by buying out his competition and screwing crooked Chicago politicians out of their local franchise rights. But monopoly didn't attract Insull because of his soul's longing for dominion, though that certainly spurred him on. It also made good business sense and, he argued, served customers better. If one larger power plant was more efficient than two smaller ones, then it stood to reason that one company owning the largest power plants possible would result in greater efficiency and lower rates than smaller plants owned by various companies vying for market share. After all, redundant infrastructure led to waste and mismanagement. Moreover, the physics of electric power favored scale; scale favored consolidation; consolidation favored monopoly; monopoly favored non-competition; non-competition favored investment; investment favored bigger power plants, which unlocked yet greater economies of scale. Insull saw this truth before any of his competitors. In pursuing it, he became the kingpin of the Chicago power business.

But this was just the beginning of his dominion. With Chicago as his home base, Insull would grow his fiefdom until it touched both coasts, remaking America in the process.

Thanks for giving a bit of publicity to the father of the grid, probably the most vilified hero of our energy history.

Very interesting and informative article. I am looking forward to reading the rest.