The Cryptid That Almost Killed a Dam

A fake fish, left politics, and environmental law

Ulysses S. Grant once described the march of history as “one goddamned thing after another.” Last week, the New York Times proved the good general right when it published a brief story about a very little, and very non-existent species of fish: the snail darter.

A biologist back in the 1970s thought that this fish, which lives in the Tennessee Valley area, was on the brink of extinction. Thanks to new research using genomics, it turns out that it’s not at all the unique species of fish scientists thought it was. Rather, it’s a stargazing darter, which is not endangered.

“There is, technically, no snail darter,” Thomas Near, curator of ichthyology at the Yale Peabody Museum, told the NYT. According to Near, earlier scientists “squinted their eyes a bit” when identifying the snail darter. Honest mistake, right? Not so fast. They were squinting their eyes on purpose.

And that’s because the myth of the snail darter was part of a massive shift in American culture and law that reformatted the country’s relationship to economic growth.

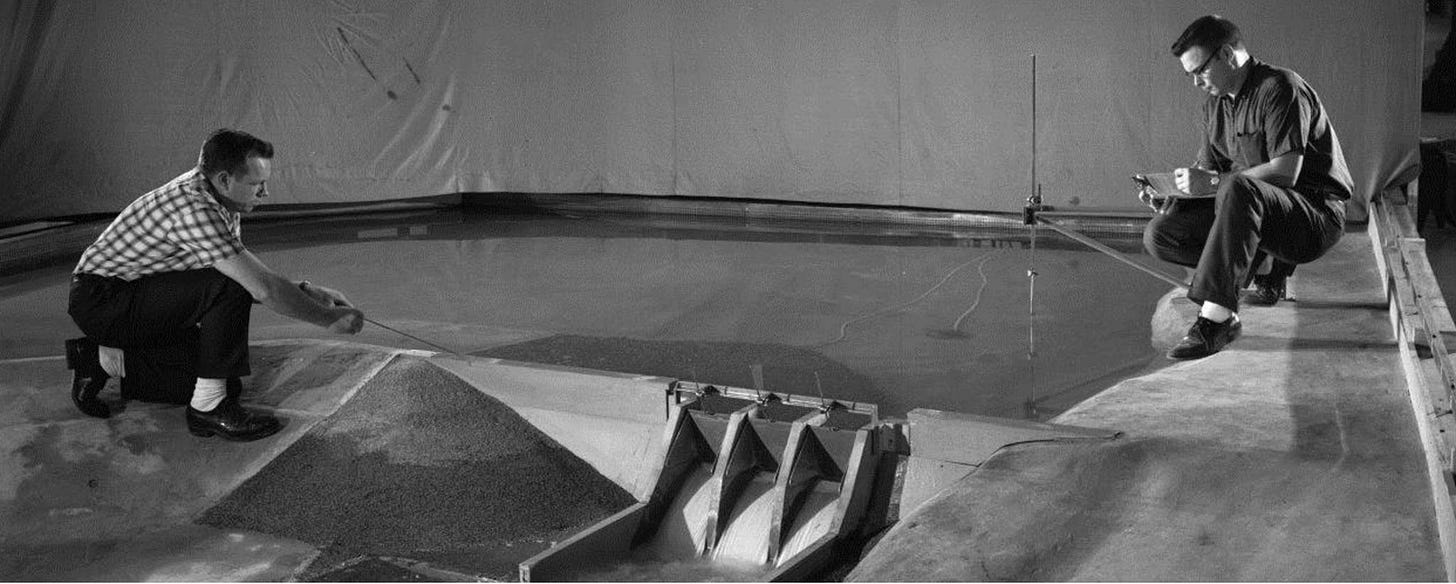

Some backstory: in the 1960s, the Tennessee Valley Authority, a New Deal project and the largest public power entity in the US, proposed building the Tellico Dam on the Little Tennessee River. For the TVA, the dam construction was old hat. The authority had, since its conception in the 1930s, built enormous power dams to electrify rural homes and power factories. Tellico was nothing new. Except for one little wrinkle: the cost-benefit ratio for Tellico, which the TVA relied upon to justify its projects, didn’t pencil out. So, the TVA found a vague, tripartite pitch for the dam that focused on recreation, land enhancement, and projected “economic benefits.”

Many within the TVA scratched their heads at this sloppy proposal and warned that opposition could be fierce. Even the Army Corps of Engineers looked askance at the dam. However, the TVA chairman at the time was committed to the idea and President John F. Kennedy helped keep Tellico alive through his support for public works projects that boosted employment numbers. Therefore, the TVA commenced to build the dam, thus planting its foot squarely into a hornet’s nest.1

The TVA had been instrumental in welding together what the historian Gary Gerstle calls “the New Deal Order,” a “constellation of ideologies, policies, and constituencies” that transcended the typical electoral time frames. A consensus, if you will. And that consensus was “founded on the conviction that capitalism left to its own devices spelled economic disaster” thus requiring “a strong central state able to govern the economic system in the public interest.”2

The New Deal Order’s ideology was a reheated version of early twentieth century Progressivism. Its constituencies were big business, government bureaucracies, and labor unions. The TVA was one of its flagship policies. Both the New Deal generally and the TVA specifically were dedicated to economic growth, class compromise, and corporatism.

By the 1960s, when the Tellico project came to life, the NDO had reached its peak, which meant it could only go downward. The fight over Tellico revealed to the TVA just how painful that descent would prove to be—a fight that lasted over decade.

While the generation that brought the TVA and the NDO into being had seen two world wars sandwich a global economic depression, their children felt less inclined to luxuriate in the highly conformist consumer society their forebears had created. Moreover, all of this economic growth seemed to come at a high price—Los Angeles lay choked in smog; small towns in Pennsylvania were so blanketed with bad air, it literally choked people to death.3

It appeared that these big industrial entities no longer had the public good in mind, but rather formed an insider’s club of CEOs and their pet political flunkies—after all, Boeing was one of the TVA’s chief allies in the fight for Tellico. These New Deal institutions needed a reboot, a watchdog. And boy did the watchdogs appear.

Over the course of the 1960s, the field of environmental law exploded, presenting the opportunity to discipline errant corporations and even the federal government itself. With the new laws came new non-profit groups funded by legacy foundations and manned by intrepid Ivy Leaguers who didn’t just want to serve some faceless corporate Borg, but craved meaning that could only come from making a difference, like the brave activists who slew Jim Crow. Scientists who wanted to bring their expertise to bear on an honorable mission joined them.

And so the slings and arrows fired upon the TVA. In 1969, the National Environmental Protection Act became law, which halted the dam’s progress two years into its construction. The TVA fought back against NEPA’s strictures until it lost in federal court and submitted to developing an Environmental Impact Statement for Tellico.

Five years later, David Etnier, a zoologist at the University of Tennessee, took a snorkeling trip with his students in the Little Tennessee River. And it was there he squinted his eyes and discovered what he believed to be the snail darter. This precious fish, Etnier realized, would surely be killed by the Tellico dam, which he already opposed. And so the environmental groups pressing their claims against Tellico now had a David to fight the TVA’s Goliath.

The ensuing legal slugfest changed forever how companies, public or private, went about building big projects. As Near told the NYT, “I feel it was the first and probably the most famous example of what I would call the ‘conservation species concept,’ where people are going to decide a species should be distinct because it will have a downstream conservation implication.”

The snail darter allowed the US Fish and Wildlife Services to combat the TVA. In 1975, USFW declared the snail darter endangered, which meant the TVA should have to halt construction. The TVA naturally disagreed and eventually found itself fighting the Department of the Interior over the issue. In 1978, with the dam 90 percent complete, the TVA lost its case before the Supreme Court and Tellico was permanently halted. Eventually, the late President Jimmy Carter signed some legislation to finish the dam, though he had previously opposed its completion.4

The TVA had not been prepared for this kind of resistance. And though it won the battle, it lost the war. The Tellico case represented the end of the NDO. The TVA, a habitually autonomous developmentalist creation of the FDR administration, confronted the newly minted regulatory state and its attendant advocacy groups and lost its public legitimacy.

With the revelation that the snail darter was another species entirely, what are we to make of what happened in this conflict? What does it tell us today?

For his part, Near told the NYT that it doesn’t matter that the snail darter was never a real species. In the end, this whole experience was a win for the actual species, the stargazing darter, which recovered from endangered status a couple of years ago. For its part, the TVA claims the dam as a win for job growth.

More interesting to me is how the sediments of time have both reinforced and shattered the competing liberal factions that fought over Tellico. As someone who came up on the Left and who engaged in socialist political activism, I never questioned the efficacy or essence of environmental law. At the same time, I championed the New Deal as exactly the kind of policy suite that could improve the country. That these two political strains ran on separate, antagonizing tracks, I never heard voiced.

Rather, a narrative emerged, a narrative of what happened to the Left, which was also an explanation of why we “couldn’t have nice things” like a new New Deal. The first part of the story involved the rise of the mid-century New Left, which differentiated itself from the Soviet-sympathetic, labor-focused Old Left (I’m being a little imprecise here for the sake of time and space) in key ways. This New Left took not the working class, which in America had been “bought off” by consumer society, but the post-colonial subject as its tribune. Thus, it not Stalin, but Mao and Frantz Fanon who appealed—especially after the horrors of the Soviet regime became clear.

This pivot also explains the rise in support for ethnno-nationalism on the Left in the 60s and 70s (so long as the ethnics weren’t white) and the popularization of the specious view that black Americans were a colony within a nation. In leaving the working class politics of the Old Left behind, the New Left introduced what we now call “identity politics.” They also injected their strivings with a romantic contempt for bigness, bureaucracy, and applied sciences like engineering.

The New Deal, as often interpreted in places like Jacobin today, was a project built around broad working class interests, not a discontinuous hodgepodge of identity groups. Thus if socialism is to regain popular appeal, then it must ditch the New Left ideas and re-embrace the FDR-style populism á la Bernie Sanders circa 2016. Perhaps the best avatar for this perspective is the scholar Adolph Reed.

Some of this is true, so far as it goes. At least, these were arguments I once made and saw others make. I still see them around. If you pepper in a little backstory about Barry Goldwater and the rise of Reagan, then you can tell yourself a tidy narrative about how the Left, thanks to the individualizing tendencies of New Left ideology, allowed itself to be seduced by the “neoliberal turn” away from New Dealism and toward free markets.

This narrative leaves out more than I can include here, but I will say it’s more of a self-soothing technique than good history. Sounder scholarship reveals one of the many blind spots beholden to this narrative line.5 In fact, it demonstrates that environmental law had its own role to play in ending the NDO and that the rise of environmental law coincided with a remarkable loss of faith in the New Deal-style of government. Even the remaining New Dealers themselves were, by the 1960s and 70s, becoming skeptical of their own achievements.

However, the New Left, with their occupations of university buildings, street theater, and terror attacks, weren’t a political force so much as a shocking, demoralizing spectacle. On the other hand, their buttoned-down peers who believed in the power of the law to end corporate, union, and bureaucratic malfeasance were the genuine article. Ralph Nader and his consumer rights advocate “Raiders” epitomize this cohort. Their aim was to reform the federal bureaucracy rather than foment revolution. In short, it was liberals, not New Left radicals, who unseated the regime established by FDR and his cohort.6

So, why don’t socialists blame the billionaire-financed liberals at the NGOs who made it functionally illegal to build anything big in this country anymore? Lots of unions jobs to be had with such projects, no? This requires a complex intellectual answer; the social and psychological answer is far simpler. Both liberals and socialists like to beat up on the New Left for what’s wrong with present-day broad Left politics because it’s easy. The Weather Underground were insane nihilists from rich families who blew up buildings. What’s to like?

Moreover, it allows liberals to pose as more moderate and sane so that they can exert discipline on the smaller faction of the Left. For socialists, pinning their current dysfunction on their New Left elders allows them tell a “rise and fall” story about themselves, a genre that offers succor because the fall is never directly your fault.

As a result, the New Left and its consequences serve as a vanishing mediator that helps tether liberals and socialists together. So long as this narrative posture survives, each can say “it wasn’t me.” And yet it binds each to each, letting them ignore what has actually distinguished them. It was the liberal revolt against the New Deal Order that shoved aside the labor-oriented socialists, but the socialists remain loyal to the social causes (like the environment) that played a role in their ideological defenestration.

Few discuss this, not just out of narrative convenience, but because, in truth, the liberals are not moderate and the socialists are not radical. Rather, both are simply competing outgrowths of the old American Progressive Movement playing out unresolved tensions inherent in that original project—an essay unto itself and for a later time.

It’s a strange game they’re playing, but that’s politics. Like plates of ice, these factions knit together, break apart, and knit back together again in response to the same undulating waves that bear back against the shore. One goddamned thing after another, indeed.

Related Articles

How to Entrench Decline: A Chicago lawsuit reveals the dark logic of climatism

Did An American Grid Operator Just Deny Climate Change? Some notes on expertise, "neutral" management, and the public square

If you would like to book me as a speaker click the button below:

Crom’s Blessing

Erwin C. Hargrove, Prisoners of Myth: The Leadership of the Tennessee Valley Authority, 1933-1990 (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1994), 171-174.

Gary Gerstle, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2022), 2-4.

Richard Rhodes, Energy: A Human History (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 293-306.

Hargove, Prisoners of Myth, 176-177.

See: Paul Sabin, “Environmental Law and the End of the New Deal Order.” Law and History Review 33, no. 4 (2015): 965–1003. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43670840 and Paul Sabin, Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism (New York, NY: WW Norton & Company, 2021). Gerstle subsumes efforts like Nader’s into the New Left. I think this is a mistake because while some overlaps exist, they hold enough in difference to warrant firm distinction. See: Gerstle, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, 8-9.

Another complicating factor is that all of this played out in the overarching domain of the mid-century “counterculture,” a phenomenon as real as it was diffuse. As the historians Peter Braunstein and Michael William Doyle quip, the counterculture seemingly “encompass[ed] any action from smoking pot at a rock concert to offing a cop.” See: Braunstein and Doyle, “Historicizing the American Counterculture of the 1960s and ’70’s” in Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s & ‘70’s (New York, NY: Routledge, 2002). Within the same volume, Andrew Kirk’s essay, “‘Machines of Loving Grace’: Alternative Technology, Environment and the Counterculture,” performs a helpful fly-by-night tour of the environmental movement’s relationship to the counterculture.

As Near told the NYT, “I feel it was the first and probably the most famous example of what I would call the ‘conservation species concept,’ where people are going to decide a species should be distinct because it will have a downstream conservation implication.”

Nicely done, Emmet. As usual.

(We thought at first the snail darter might be a segue to the delta smelt/current events.)

Interested to read your take on the progressivist movement in America. Thank you for the thought provoking stack here.